But while writing a book about the publishing of American literature in England, I was surprised to find that some of the most popular US writers stayed in Kentish Town. They were hosted in a house on Grove Terrace by their English publisher, Sampson Low Jr.

As a partner in his father’s firm, Sampson Low, Son & Co, he published English editions of some of the best-selling American books of the nineteenth-century. Kentish Town was an ideal location for him – close enough to his business in Fleet Street, but quiet enough for a man described as a “chronic invalid” by his business partner.

Online records of the National Archives don’t reveal when Low Jr moved to Grove Terrace, but it was after his marriage in 1853, and before 1856, when reports from his American visitors start appearing. Baptismal records show that his son, also Sampson, was christened at St Anne’s Church on Highgate Hill in 1859.

The lack of an international copyright agreement between England and the US aided sales of American books. Until 1854, an American book could only be copyrighted in England if it was published here first. After that year, an author could only have a copyright if they were resident in British territory at the time of publication.

The law meant that most American books could be freely reprinted in Britain without payment to or permission from their authors. This situation was great for readers, who got cheap new titles, but less so for American authors and the British publishers who tried to make agreements with them.

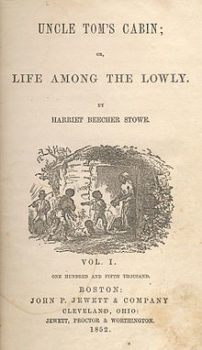

In late summer 1852, Sampson Low Jr had a stroke of luck that allowed him to capitalize on the boom in American writing. He was in America when Uncle Tom’s Cabin became an unprecedented success in England. He called on Stowe and secured her future books for his firm, just beating another English publisher who was walking up the path to Stowe’s house as he was leaving.

But there was a problem. Uncle Tom’s Cabin had been wildly successful, but because it had no English copyright, many publishers had issued editions. Sampson Low wanted exclusive rights to her next book Dred – another anti-slavery novel – so in 1856 the firm asked Stowe to come to England to publish her book and secure a copyright. It proved worth it: Dred went on to sell fifty thousand copies in the first two weeks. The firm would replicate this arrangement with other authors, and Sampson Low Jr’s house in Grove Terrace was an ideal place to host these American visitors.

Stowe spent time in Low Jr’s house in Grove Terrace in October 1856. Preferring what she called “the postscripts of London” to the city centre, she would have enjoyed her surroundings. But unfortunately, she doesn’t describe the stay in any detail.

In letters to her mother, held at the University of Virginia, Cummins explains the geography of north London: “Hampstead, where I go on Wednesday, is one suburb, as Kentish Town is another.” She admired the Grove Terrace residence, observing that the Lows “live in a neat and simple style” and “whatever I see or do with them, I am sure it will be in the best mode.”

Finding that the London air improved her health, she took “a real English walk” on Hampstead Heath, interrupted by that most English of weathers, an April shower. Like today’s residents, Cummins also took advantage of Kentish Town’s proximity to Regent Street, where she marvelled at the “pretty things” that London had to offer, and indulged in a new bonnet.

What Cummins enjoyed most about her stay in was the hospitality. “I came here on business,” she wrote, “but that relation seems totally lost in one of friendship and hospitality”.

The story is cut short: Low Jr died in 1872, buried in Highgate Cemetery. And the archives of Sampson Low, Son & Co were destroyed in the Blitz, with only scattered snippets surviving. Yet even these show how Grove Terrace played a key role in the cultural “special relationship” between Britain and the United States.

Dr Katie McGettigan is a researcher in the Department of American and Canadian Studies at the University of Nottingham

Please support us if you can

If you enjoyed reading this, perhaps you could help out? In November 2021, Kentishtowner will celebrate its 11th birthday. But with the sad demise of our free independent monthly print titles due to advertising revenues in freefall, we need your support more than ever to continue delivering cultural stories that celebrate our neighbourhood. Every contribution is invaluable in helping the costs of running the website and the time invested in the research and writing of the articles published. Support Kentishtowner here for less than the price of a coffee – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.