It all happened in an engine shed. If there was a time and place when Camden Town became cool, it was at the Roundhouse one October evening in 1966. Fifty-five years ago, in fact.

That was the moment when psychedelia came into style and Camden gained the counter-culture credentials which, in very different fashion, are still reflected in the stalls around Camden Lock. The venue for that political, musical, cultural conjuncture was, fittingly perhaps, a legacy of the defining aspect of the old, soot-ridden Camden: the railways.

The construction of the main rail lines turned early Victorian Camden Town upside down carving a huge swathe through the area. Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son, published in the second half of the 1840s, took as one of its themes the intrusion of the railways into a part of London he knew well. It was, he wrote, “a great earthquake … Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground.” It sounds like HS2!

Just as Dombey and Son was appearing in serialised form, the Roundhouse was being built as a locomotive shed, complete with a turntable which gave the building its name and shape. That turntable was only used for about a decade, because the engines got too big. It then became a warehouse, notably for Gilbey’s gin; and eventually fell derelict.

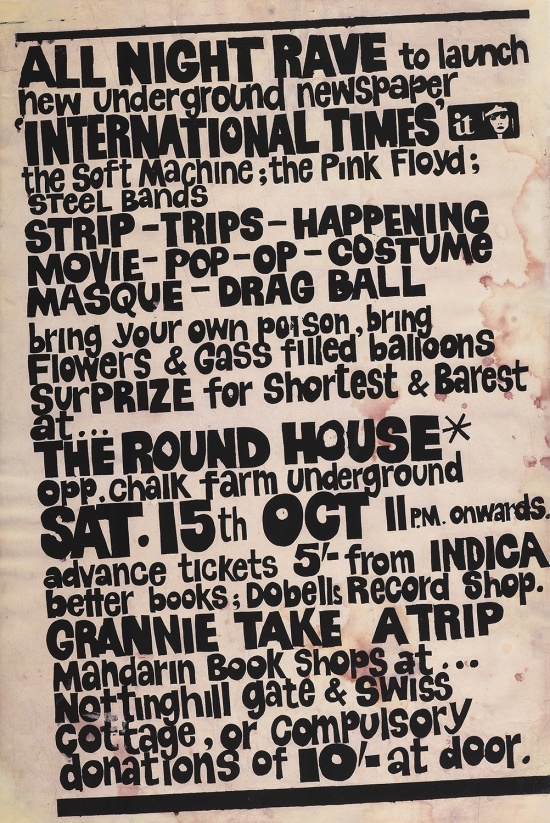

The renaissance of the Roundhouse started in 1964 when the playwright Arnold Wesker launched Centre 42, winning trade union support for the creation of an arts and cultural centre. But the moment that Camden became hip was two years later, on 15th October 1966 – when Pink Floyd and Soft Machine, neither then signed up to a record label, played at the all-night launch party of International Times (IT), one of the more cerebral ventures of the sixties alternative press.

It was the first big gig ever held at the Roundhouse. The building wasn’t remotely fit for purpose, as Barry Miles, a founder of IT, recalled in his history of the city’s counter-culture, London Calling:

“There was no proper floor, and great jagged pieces of metal stuck up through a layer of grime. There were only two toilets, and the electricity supply was about the same as that of a small house … the entrance staircase from Chalk Farm Road was so narrow that only one person at a time could enter or leave.”

On that night, 2,000 youngsters made their way up and down that far-from-adequate stairwell. But the venue delivered. “It was great,” recalls top record producer Joe Boyd. “Very raw, unheated – but strangely spectacular.”

The ‘shortest/barest’ contest – what a stark reminder of the sexist side of psychedelia – was won, Miles recalls, by Marianne Faithfull, “for an extremely abbreviated nun’s outfit”. Mini-skirted women handed out lumps of sugar – they weren’t laced with LSD but some went on a trip all the same. A motorcycle weaved in and out of the audience, revving in sync with the music.

And on the stage? “The Pink Floyd, psychedelic pop group,” – reported IT in its second issue – “did weird things to the feel of the event with … slide projections playing on their skin … spotlights flashing in time with the drums.” It was one of the first psychedelic light shows.

Dianne Lifton, then a 21-year-old fashion designer, is fairly sure she was at the IT launch – but then, as folks say, if you can remember it, you weren’t there. “I was rebellious, up for anything and living in Camden Town. It wasn’t yet swinging London, but it was the time of Arts Laboratories and experimental happenings, and the Roundhouse was one of the alternative venues we used.”

She has a clearer recall of the New Year’s Eve event of “psyche-kinetic destruction” a few weeks later, with an even more stellar line-up, including The Who, “pioneers of destructive pop” and Pink Floyd.

While the bands played, Di and a friend – at the behest of an artist – drove a silver-sprayed Cadillac into the auditorium. “I was both excited and terrified” – the terror coming from driving into crowds who were facing the other way, standing and dancing near the stage. “We were both dressed from head to foot in silver – soft helmets, in vogue at the time, silver mini culottes and silver tights. Bringing the car to a standstill at the foot of the stage, we both got out carrying large axes and began to smash the car. Friends standing round us were unable to hold back the crowds, some of whom wanted to stop us while others wanted to help and grabbed the axes from us.”

The Roundhouse quickly became the counter-culture’s venue of choice. Two years later Compendium opened a short distance away, selling beat poetry, obscure anarchist papers and a lot more. It remained there until 2000 when the shop became a Dr Martens. A Sunday crafts market got going at Camden Lock in the early seventies, which developed, into the Camden market scene of today.

What a transformation. The loos are better, and the stairs a whole load safer, at the Roundhouse these days – and happily, once lockdown is over, it will continue to be a great place for music and performance.

Article originally published 2016, updated March 2021