I

n 1961, at the age of 27, my father, Jonathan Miller, was in a comedy show called Beyond the Fringe with Alan Bennett, Dudley Moore and Peter Cooke. With its success my father took a pile of reviews to his bank and convinced them to lend him the money to buy a house in a somewhat shabby and forgotten corner of London’s NW1.

The street, Gloucester Crescent, was relatively unknown at the time, but in the coming years it was to become one of the most talked and written about streets of Sixties London. With Regent’s Park Terrace, which joined the two ends of the Crescent, it became the home of a growing collection of like-minded and competing writers, journalists, musicians and academics.

As an impressionable child the centre of this community were of course my parents, Jonathan and Rachel Miller along with the ever-present figure of my father’s comedy partner and playwright Alan Bennett. Alan started his life in the Crescent as my parent’s lodger eventually buying the house across the road. Next to him were the novelist Alice Thomas Ellis (aka Anna Haycraft) and her publisher husband Colin Haycraft.

Others in the street were the jazz singer and writer George Melly and his wife Diana who later sold their house to Mary-Kay Wilmers, ex-wife of film director Stephen Frears. Across from the Mellys were the artist David Gentleman and the Labour MP Giles Radice, and two doors away, the writer Claire Tomalin and her journalist husband Nick. He was killed in Israel in 1973 by a Syrian missile while reporting on the Yom Kippur War, and she later married the playwright Michael Frayn, who in turn moved into the Crescent.

Three doors from our house was the widow of Ralph Vaughan Williams, Ursula, and across from her the artistic director of the Royal Court, Max Stafford-Clark who lived with his wife Ann and her son from the film producer Sam Spiegel. Immediately behind us in Regent’s Park Terrace was the eminent philosopher Sir A.J. Ayer and his American wife, author and broadcaster Dee Wells. Next to them, Shirley Conran and her sons Jasper and Sebastian. Further along the Terrace were the writers Angus Wilson, V.S. Pritchett and A.N. Wilson.

here was of course Miss Shepherd, who claimed to be on the run from the police and spent the next eighteen years hiding from them a van in Gloucester Crescent. In an attempt to disguise the van she would regularly repaint it in varying shades of yellow. On early mornings, she could be seen cajoling the dustmen, and various residents, to push her van to a new spot in the street convinced that that too would confuse the police.

Eventually Camden council imposed residents parking on the Crescent and Alan Bennett was hoodwinked into offering Miss Shepherd and her van refuge in his driveway – there she remained for the next ten years. Years after her death she became the subject of one of Bennett’s plays and then film, The Lady In The Van, starring Maggie Smith.

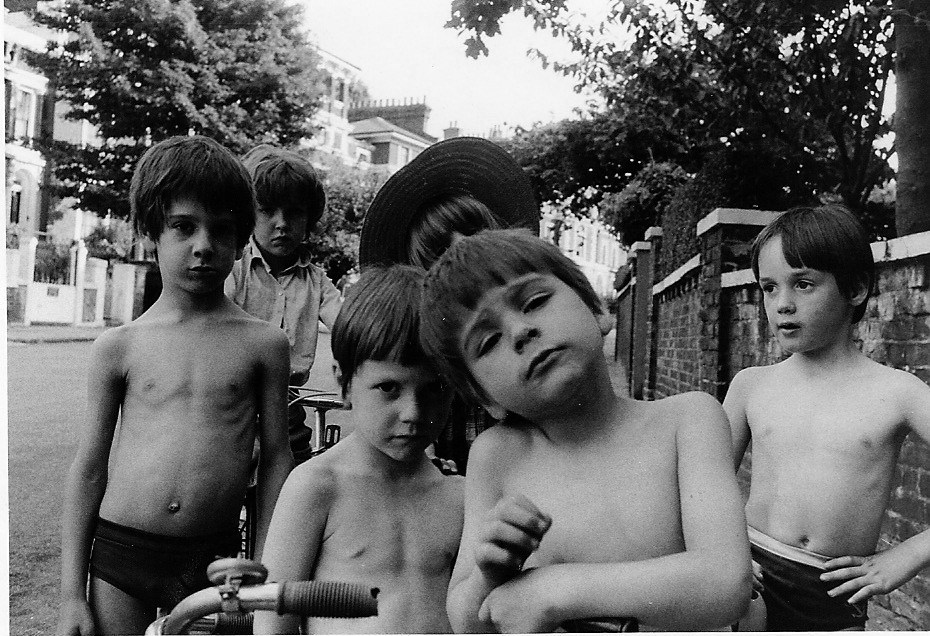

Over the coming decades, great friendships were made, professional rivalries were fought and terrible fallouts took place, but in the middle of it all, throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s, were the children of the Crescent. We were the cement of this community – we crossed boundaries, transcended the professional rivalries of parents and climbed over garden walls to make lifelong friendships.

We shared schools, kitchen tables, bedrooms and holidays and spent hours in each other’s houses crossing the invisible boundaries that our parents unconsciously created with their rivalries. My closest friends had parents much like mine: educated at the same small collection of public schools and knowing each other well from either Oxford or Cambridge and then through their work. Together they’d found a common and worthy cause to believe in, borne out of the post-war euphoria of the 1945 Labour landslide, which created a radical new way of thinking which promised a fairer society.

his led our parents to become left-leaning, idealistic as well as anti-establishment, with a strong distaste for the old-school approach to authority and power. Every one of the parents in the street made the conscious decision to give their children a radically different childhood to their own and packed us off to the local state schools where we could mix with children from every walk of life, and encouraged to be free spirited. We were frequently left to our own devices whilst our parents went off to expand their utopian visions and pursue glittering careers.

For me, Gloucester Crescent has always been home but one with a bigger story to tell: this is my story of growing up in the community as I explored and pushed boundaries to find an identity in a world of creative titans.

Main image: Gloucester Crescent, 1970s